4 Everything about Unix/Linux they didn’t teach you

In this section, I want to talk about some basic setup in order to interact with an HPC system.

4.1 Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Setup your terminal to connect to an HPC system

- Find and set environment variables in an HPC system

- Modify your

$PATHvariable to include the path to an executable - Use

whichto identify which version of an executable you’re using - Explain built-in utilities that are useful in your work

4.2 Terminal setup

If you are on Linux/Mac, you’ll be working with the terminal. On Windows, you’ll need a terminal program such as PuTTY to connect to the remote servers.

In our examples, we’re going to be connecting to the Fred Hutch servers rhino and the associated cluster, gizmo.

Many HPC systems are behind an organization’s VPN, so you’ll need a VPN client like Cisco Secure Client to get into your VPN.

FH Users: after connecting through the Fred Hutch VPN you’ll connect to rhino to gain access to the HPC system.

If you are on Windows, you can install Windows Subsystem for Linux, and specifically the Ubuntu distribution. That will give you a command-line shell that you can use to interact with the remote server. I prefer this route, but PuTTY works great as well.

On your machine, I recommend using a text editor to edit the scripts in your remote shell. Good ones include Visual Studio Code (VS Code), or built in editors such as nano. You can use VSCode to edit scripts remotely using the SSH extension. Editing scripts remotely like this may be more comfortable for you. Note that if you are on a Windows machine that is remotely administered, you will need to contact the admins to enable the OpenSSH extension in Windows for it to work.

4.3 hostname: What machine am I on?

One of the most confusing things about working on HPC is that sometimes you have a shell open on the head node, but oftentimes, you are on a worker node.

Your totem for telling which node you’re in is hostname, which will give you the host name of the machine you’re on.

For example, if I used grabnode to grab a gizmo node for interactive work, I can check which node I’m in by using:

hostnamegizmok164If you’re confused about which node you’re in, remember hostname. It will save you from making mistakes, especially when using utilities like screen.

4.4 Environment Variables

Environment variables are variables which can be seen globally in the Linux (or Windows) system across executables.

You can get a list of all set environment variables by using the env command. Here’s an example from my own system:

envSHELL=/bin/bash

NVM_INC=/home/tladera2/.nvm/versions/node/v21.7.1/include/node

WSL_DISTRO_NAME=Ubuntu

NAME=2QM6TV3

PWD=/home/tladera2

LOGNAME=tladera2

[....]One common environment variable you may have seen is $JAVA_HOME, which is used to find the Java Software Development Kit (SDK). (I usually encounter it when a software application yells at me when I haven’t set it.)

You can see whether an environment variable is set using echo, such as

echo $PATH/home/tladera2/.local/bin:/home/tladera2/gems/bin:/home/tladera2/.nvm/versions/node/v21.7.1/bin:/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin:/usr/games:/usr/local/games:/ [....]Since we’re mostly going to be working in a Unix environment, we’re not going to touch on Windows environment variables. However, there is also a $PATH environment variable that you can set.

I recommend looking at the PowerShell documentation for more information about Windows-specific environment variables

4.4.1 Setting Environment Variables

In Bash, we use the export command to declare an environment variable. For example, if we wanted to declare the environment variable $SAMTOOLS_PATH we’d do the following:

# works: note no spaces

export SAMTOOLS_PATH="/home/tladera2/miniconda/bin/"One thing to note is that spacing matters when you declare environment variables. For example, this won’t declare the $SAMTOOLS_PATH variable:

# won't work because of spaces

export SAMTOOLS_PATH = "/home/tladera2/miniconda/bin/"Another thing to note is that we declare environment variables differently than we use them. If we wanted to use SAMTOOLS_PATH in a script, we use a dollar sign ($) in front of it:

$SAMTOOLS_PATH/samtools view -c $input_fileIn this case, the value of $SAMTOOLS_PATH will be expanded (substituted) to give the overall path:

/home/tladera2/miniconda/bin/samtools view -c $input_file4.4.2 A Very Special Environment Variable: $PATH

The most important environment variable is the $PATH variable. This variable is important because it determines where to search for software executables (also called binaries). If you have softwware installed by a package manager (such as miniconda), you may need to add the location of your executables to your $PATH.

We can add more directories to the $PATH by appending to it. You might have seen the following bit of code in your .bashrc:

export PATH=$PATH:/home/tladera2/samtools/In this line, we are adding the path /home/tladera2/samtools/ to our $PATH environment variable. Note that how we refer to the PATH variable is different depending on which side the variable is on of the equals sign.

TLDR: We declare the variable using export PATH (no dollar sign) and we append to the variable using $PATH (with dollar sign). This is something that trips me up all the time.

In general, when you use environment modules on gizmo, you do not need to modify your $PATH variable. You mostly need to modify it when you are compiling executables so that the system can find them. Be sure to use which to see where the environment module is actually located:

which samtools

4.4.3 Making your own environment variables

One of the difficulties with working on a cluster is that your scripts may be in one filesystem (/home/), and your data might be in another filesystem (/fh/fast/). And it might be recommended that you transfer over files to a faster-access filesystem (/fh/temp/) to process them.

You can set your own environment variables for use in your own scripts. For example, we might define a $TCR_FILE_HOME variable:

export TCR_FILE_HOME=/fh/fast/my_tcr_project/to save us some typing across our scripts. We can use this new environment variable like any other existing environment variable:

#!/bin/Bash

export my_file_location=$TCR_FILE_HOME/fasta_files/4.4.4 .bashrc versus .bash_profile

Ok, what’s the difference between .bashrc and .bash_profile?

The main difference is when these two files are sourced. bash_profile is used when you do an interactive login, and .bashrc is used for non-interactive shells.

.bashrc should contain the environment variables that you use all the time, such as $PATH and $JAVA_HOME for example.

You can get the best of both worlds by including the following line in your .bash_profile:

source ~/.bashrcThat way, everything in the .bashrc file is loaded when you log in interactively.

4.5 Working with Shell Scripts

Note that I’m only covering bash scripting (hence the name of the book). Each shell has different conventions.

When you are writing shell scripts, there’s a few things to know to make them executable.

4.5.1 The she-bang: #!

If you’ve looked at a shell script and seen the following:

#| filename: samcount.sh

#!/bin/bash

samtools view -c $1 > $1.counts.txtthe #! is known as a she-bang - it’s a signal to Linux what shell interpreter to use when running the script on the command line.

4.5.2 Making things executable: chmod

Now we have our shell script, we will need to make it executable. We can do this using chmod

chmod +x samcount.shNow we can run it using:

./samcount.sh bam_file.bamBecause the script is not on our $PATH, then we need to specify the location of the script using ./.

Note that you can always execute scripts using the bash command, even if they’re not executable for you on your filesystem. You will still need read access.

bash samcount.sh bam_file.bamMuch more info about file permissions is here: Permissions (at the Carpentries)

4.5.3 User Access: Groups

The groups that you are a member of essentially control access to other files that you don’t own.

You can see which groups you are a member of by using groups. For example, on my local Windows Subsystem for Linux filesystem, I am a member of the following groups.

groupstladera2 adm dialout cdrom floppy sudo audio dip video plugdev netdevAs an HPC user, you will usually not have root-level access to the cluster. Again, because it is a shared resource, this is a good thing. The trick is knowing how to install software and add it to your path, or run software containers with new software on a shared system.

When we talk more about software environments, we’ll talk about Docker.

Docker requires root-level access to run processes on a machine. There is a special docker group that has pretty much root-level access.

On a shared system such as an HPC cluster, we don’t want to grant such access to individual users.

Enter Apptainer, which was designed for HPC clusters from the ground up. You can run Docker/Apptainer containers on a shared system without needing root-level access.

4.6 Useful Utilities

The following section outlines some useful unix utilities that can be very helpful when you’re working in bash. Most of these should be available in HPC systems by default.

4.6.1 Text editors: vim or nano

In general, we recommend connecting an editor such as VS Code with the SSH extension to make it easier to edit files. But sometimes you just need to edit a file on the system directly.

That’s what nano and vim are for. Of these, nano has the smallest learning curve, since it works like most editors. vim is powerful (especially for searching and substitution), but there is a steep learning curve associated with it.

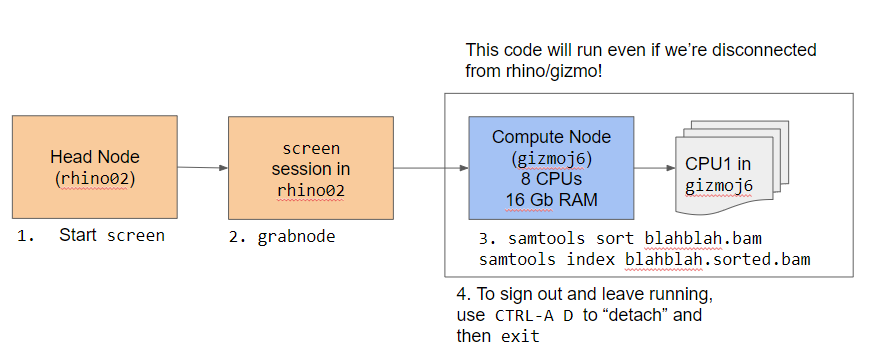

4.6.2 screen or tmux: keep your session open

Oftentimes, when you are running something interactive on a system, you’ll have to leave your shell open. Otherwise, your running job will terminate.

You can use screen or tmux, which are known as window managers, to keep your sessions open on a remote machine. We’ll talk about screen.

screen works by starting a new bash shell. You can tell this because your bash prompt will change.

The key of working remotely with screen is that you can then request an hpc node.

For FH users, you can request a gizmo node using grabnode. We can then check we’re on the gizmo node by using hostname.

If we have something running on this node, we can keep it running by detaching the screen session. Once we are detached, we should check that we’re back in rhino by using hostname. Now we can log out and our job will keep running.

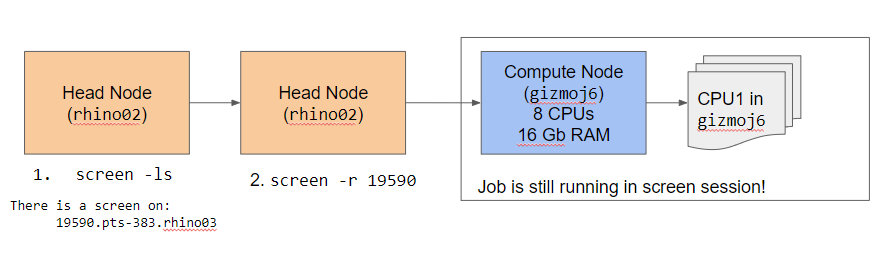

If we need to get back into that screen session, we can use:

screen -lsTo list the number of sessions:

There is a screen on:

37096.pts-321.rhino01 (05/10/2024 10:21:54 AM) (Detached)

1 Socket in /run/screen/S-tladera2.Once we’ve found the id for our screen session (in this case it’s 37096), we can reattach to the screen session using:

screen -r 37096And we’ll be back in our screen session! Handy, right?

Note that if you logout from rhino, you’ll need to log back into the same rhino node to access your screen session.

For example, if my screen session was on rhino01, I’d need to ssh back into rhino01, not rhino02 or rhino03. This means you will need to ssh into rhino01 specifically to get back into your screen session.

4.6.3 The Tab key

Never underestimate the usefulness of the tab key, which triggers autocompletion on the command line. It can help you complete paths to files and save you a lot of typing.

4.6.4 squeue -u <username>

Sometimes you will want to know where you are in the queue of all the other jobs that are in the run queue in SLURM. You can use squeue with -u (username) option to look for your username. For example:

squeue -u tladera2